University of Cambridge

Cambridge, UK

Owing to the dispersed pattern of higher education as delivered at the University of Cambridge, there is no central campus for teaching, instead direct tuition is provided within colleges and at departments distributed around the city. Unlike the centralised model of teaching familiar to modern universities, i.e collective mass learning environments at a compact campus, the Oxbridge model relies on one-to-one supervisions and small seminar groups. This model pervades today, however, post-war alterations to higher education priorities and university expansion necessitated a concentrated environment for the university’s arts and humanities faculties. Thus the Sidgwick Site was established on the far side of the river Cam from the historic colleges as a new campus for the collegiate university.

The Sidgwick Site, built to a masterplan from Casson and Conder, began work in 1952 as a framework containing faculty buildings, staff offices and lecture halls, amongst some recreation amenities. The ‘controlling framework’ which was to guide later development of individual buildings is based on typology of the Cambridge college, whose urban form is derived from the individual arrangement of linear ranges around large rectangular courts. The Sidgwick Site masterplan shows symptoms of this ‘courtyarditis’, a label applied to the later Churchill College Competition, also in Cambridge, where most entrants returned to the familiar collegiate pattern of linked quadrangular courts to symbolise the space of academia.

Despite the opportunity and the conditions to propose an ideal geometric layout over the site, (the site consisted of flat former agricultural land) Casson and Conder deliberately eschewed any formal axes or frontal vistas typically associated with new build campuses. Their morphological mutation of the Cambridge college type turned out to be particularly modern in its urban form, at a time when Cambridge was only just turning to reluctantly accept modernism.

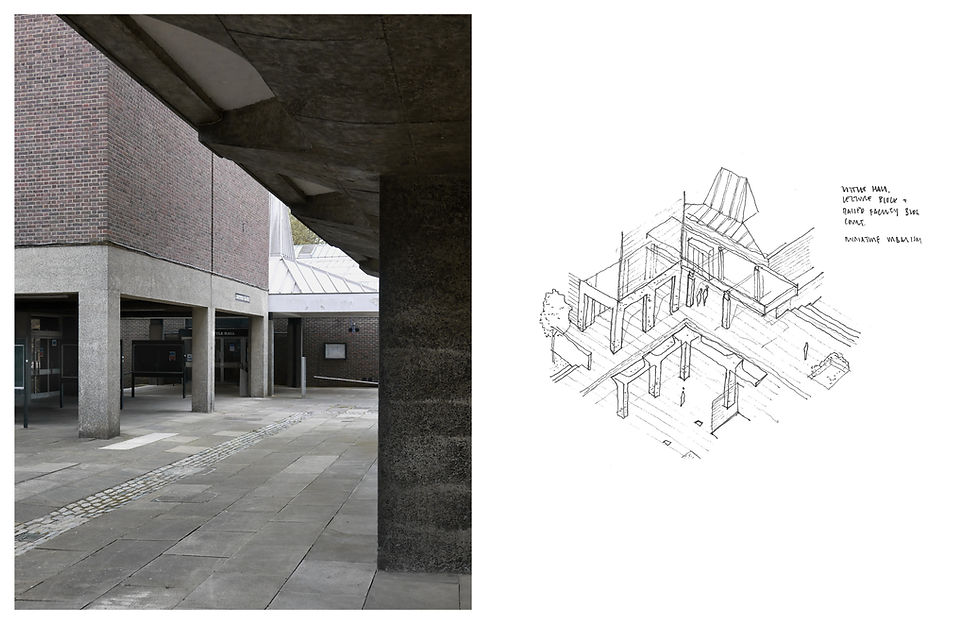

In place of completely contained quadrangles, the organisation of linear blocks cranked at 90 degrees in such a way that blocks would each partially enclose courts enabled the college court arrangement without any single structure fully closing the quadrangle. As such, multiple architecturally individuated buildings contribute towards making a court as part of a heterogenous environment. Smaller special buildings are points of exception within the orthogonal layout of linear blocks. Lecture buildings form freestanding objects in space, providing deviations in the logic of the plan, they are differentiated by sculpted silvery hats in contrast to the dark brick and concrete masses of the faculty buildings.

At the Sidgwick Site the ground plane is preserved as a precinct formed of multiple scales, types and character of courts raised atop a permeable pedestrian plinth. Whilst the original masterplan inferred a mat building configuration of closely bounded spaces typical of a Cambridge college, the raising of the faculty buildings to establish a continuous plane enables the simultaneous enclosure of the court, and the extension of the public realm beneath the blocks. The U-shaped Raised Faculty Building forms three sides of a main court whilst creating an open arcade of massive concrete piloti which act as a filter between the interior of the court and the extension of the continuous ground plane beneath.

The immense main court is linked on a diagonal axis to a series of gradated courts which diminish in scale to form verdant courts on an intimate scale. These courts are formed by the orthogonal arrangement of linear buildings which appear to slip past each other and casually abut one another, creating pockets with an altogether more incidental spatial character. The rather acropolitan plateau which the Raised Faculty Building dominates steps down to a series of small courts. Proceeding from one court to the next the pedestrian is funnelled through a sequence of porches and covered arcades at the entrances to each building, which creates a rhythm of compression and release.

The unimpeded podium on which the faculty buildings are arranged elevates the public dimension of the campus and restricts vehicles to the perimeter creating an academic precinct as a place apart. The containment of the courtyard type, coupled with the porosity of the ground plane enable situational space without compromising the accessibility of the campus, dissolving the insularity associated with the Cambridge college. Here the academic preserve is made urban by virtue of its elevation of the pedestrian.

Unfortunately, only the south area was completed according to the Casson and Conder framework and later buildings were not aligned to the urban concept initially established. The urban pattern of concatenated courts radiating from the focal main court is lost in the ill-defined space between individual monumental buildings by later architects. The coherence and sense of enclosure of the original south section of the Sidgwick Site diminishes amongst more recent buildings of fragmented orientation and morphology whose dissonance undermines the totality of the campus as a comprehensively conceived academic environment.

Comments